Booting a macOS Apple Silicon kernel in QEMU

I booted the arm64e kernel of macOS 11.0.1 beta 1 kernel in QEMU up to launchd. It’s completely useless, but may be interesting if you’re wondering how an Apple Silicon Mac will boot.

Howto

This is similar to my previous guide on running iOS kernel in QEMU:

- install macOS 11.0.1 beta 1 (20B5012D)

- run

build_arm64e_kcache.shto create an Apple Silicon Boot Kext Collection - build the modified QEMU:

git clone https://github.com/zhuowei/qemu cd qemu git checkout a12z-macos mkdir build cd build ../configure --target-list=aarch64-softmmu make - create a modified device tree by running DTRewriter on iPad Pro firmware:

python3 extractfilefromim4p.py Firmware/all_flash/DeviceTree.j421ap.im4p DeviceTree_iPad_Pro_iOS_14.0_b3.devicetree java DTRewriter DeviceTree_iPad_Pro_iOS_14.0_b3.devicetree DeviceTree_iPad_Pro_iOS_14.0_b3_Modified.dtb - run QEMU:

./aarch64-softmmu/qemu-system-aarch64 -M virt -cpu max \ -kernel /path/to/bootcache-arm64e \ -dtb /path/to/DeviceTree_iPad_Pro_iOS_14.0_b3_Modified.dtb \ -monitor stdio -m 6G -s -S -d unimp,mmu \ -serial file:/dev/stdout -serial file:/dev/stdout -serial file:/dev/stdout \ -append "-noprogress cs_enforcement_disable=1 amfi_get_out_of_my_way=1 nvram-log=1 debug=0x8 kextlog=0xffff io=0xfff serial=0x7 cpus=1 rd=md0 apcie=0xffffffff" \ -initrd /path/to/ios14.0b3/ramdisk.dmg $@ - run gdb with this script:

~/Library/Android/sdk/ndk/21.0.6113669/prebuilt/darwin-x86_64/bin/gdb \ -D /any/emptydir \ -x bootit.gdbscriptcontinue

And the macOS kernel will boot into launchd.

Is this useful?

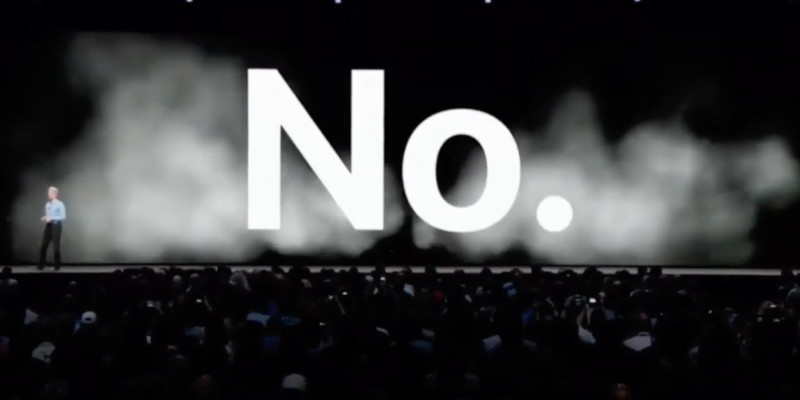

No:

- Absolutely nothing is supported: literally only the kernel and the serial port works, not even the userspace since there’s no disk driver

- Userspace is instead borrowed from iOS 14 b3

- This will never boot anything close to graphical macOS UI

- Most importantly, even if I ever managed to fully boot the macOS kernel, emulating macOS is useless anyways.

There are only three reasons I can think of for emulating macOS: security research, software development without a real Apple Silicon machine, and Hackintoshing. This approach will help with none of these:

- Emulating iOS is useful for security research when jailbreak is not available. Apple Silicon Macs already support kernel debugging.

- Not useful for software dev: QEMU’s CPU emulation doesn’t support Apple Silicon-specific features, such as Rosetta’s memory ordering or the APRR JIT.

- as for Hackintosh: macOS uses CPU instructions that aren’t available yet on non-Apple ARM CPUs, so you can’t have hardware accelerated virtualization, only very slow emulation. Besides, Hackintoshes are often built when Apple’s own hardware isn’t fast enough; in this case, Apple’s ARM processors are already some of the fastest in the industry.

I researched this this not because it’ll be practical, but only to understand how an Apple Silicon Mac works. This will never be a Time Train: only a science experiment.

What I did

Create kext collection

On iOS, the kernel and its Kexts are packed together into a bootable file called the Kernel Cache.

macOS 11 uses an evolved version of this format, called the Boot Kext Collection.

Like the iOS kernelcache, it contains all Kexts required for booting, so the bootloader only needs to load it into memory and jump into it.

To create a boot kext collection, macOS 11 introduces the kmutil tool.

Here’s my script to get kmutil to generate an arm64e kext collection.

It manually excludes some kexts because they cause kmutil to error out. Most are because they depend on ACPI, which is not available on Apple Silicon. I made a script to detect them.

Debugging kmutil failures on macOS 11 beta 3 was easy because it dumped out the entire NSError message. However, on macOS 11.0.1 beta, Apple decided to hide the full error message and only print an error code. I had to disable SIP and put a breakpoint on swift_errorRetain to get at the underlying error.

Once the build_arm64e_kcache.sh runs, a Boot Kext Collection is created at ~/kcache_out/bootcache-arm64e, which can be booted in QEMU.

Disassembling the boot kext collection

For debugging, I also had to disassemble the newly created Boot Kext Collection in Ghidra.

Unfortunately, Ghidra isn’t updated for macOS 11 and will refuse to load the file, first giving an error about XML DOCTYPE, then - once that’s worked around - an IOException from the invalid ntools value in the LC_BUILD_VERSION load command.

I created a script to fix up the kext collection so that Ghidra can load it.

Note that this is still not perfect - Ghidra still doesn’t fixup pointers or read symbols.

To get method names, I also disassembled the raw kernel file (/System/Library/Kernels/kernel.release.t8020) for cross reference. Note that the raw kernel is based at a different address - you can either rebase it in Ghidra, or just be careful to convert addresses.

Disable PAC

I already had a modified QEMU to boot an iOS kernel (which has inspired others, such as Aleph Security, to build much better open-source iOS emulation platforms)

In early 2019 I updated my modified QEMU to work with PAC for the iPhone Xs/Xr.

QEMU by that time already supported PAC instructions; however, Apple modified the crypto algorithm when implementing PAC, so the kernel fails to boot.

I decided to instead turn PAC instructions into no-ops, since I don’t know how Apple’s algorithm worked. This also makes it easier to debug the kernel.

Since the macOS DTK used an A12z processor, the modified QEMU just worked.

Device tree

Like iOS, macOS on Apple Silicon uses a device tree to describe hardware to the kernel, and to pass boot arguments.

macOS 11.0.1 beta’s installer doesn’t contain a device tree for the DTK: I suspect it would be in the .ipsw files, which are not publically available. Instead, I borrowed the iPad Pro’s device tree from iOS 14 beta 3.

Like the iOS in QEMU experiments, I first disabled every piece of hardware in the device tree except the serial port.

Unlike iOS, macOS expects some more information in the device tree:

- ram size (since Macs have upgradeable RAM)

- nvram, otherwise panics with a null pointer while reading nonce-seed. (I copied nvram from bazad’s dump of an iPhone device tree.)

- AMCC (KTRR) register positions

- System Integrity Protection status

I rewrote my device tree editor to allow populating these extra params.

Up to launchd

I can’t actually boot a macOS root filesystem as I don’t have an emulated hard disk.

I don’t have a recovery ramdisk either: that would likely only be included in the DTK IPSW, which is not public.

Instead, I decided to boot with an iOS ramdisk to test the kernel, and disable signature checking using a GDB breakpoint.

I also couldn’t get the trustcache (list of executables trusted by the kernel) to load. I tried following Aleph Security’s guide, but macOS 11 is more strict than iOS 12 and needs it below the kernel; I couldn’t figure out the correct memory address.

Why it took so long

I actually had this blog post ready since August 9th, but I spent an extra 3 months trying to fix issues, since I really wanted to at least get to a shell!

Unfortunately:

- debugging why drivers wasn’t loading was hard

- I couldn’t disable signature checking properly

- I wanted to wait until Apple released an A14 kernel instead of the DTK’s A12, so that we can look at how virtualization works, but they never did

It’s now November 9th and Apple’s holding their press conference tomorrow: so it’s now or never.

What’s left

I’m probably not going to be working further on this, but here’s what one can do to make this an actual useful research platform:

- Figure out why half the drivers aren’t loading at all

- Write basic drivers/emulations:

- probably emulate AIC in QEMU (based on Project Sandcastle’s Linux driver) since a custom interrupt controller Kext would be hard to write

- port Apple’s old PowerPC PCIE drivers, since it’s too hard to emulate the Apple Silicon PCIE controller. This will allow us to connect a virtual hard drive.

- Switch to the A14 kernel when Apple releases Apple Silicon Macs, so we can test virtualization

What I learned

- How to modify QEMU to disable PAC

- How iBoot on Apple Silicon passes boot options in the device tree

- How to generate an Apple Silicon kernel cache without an Apple Silicon Mac

- How to fight

kmutilfor the real error message - Never procrastinate on a blog post for three months